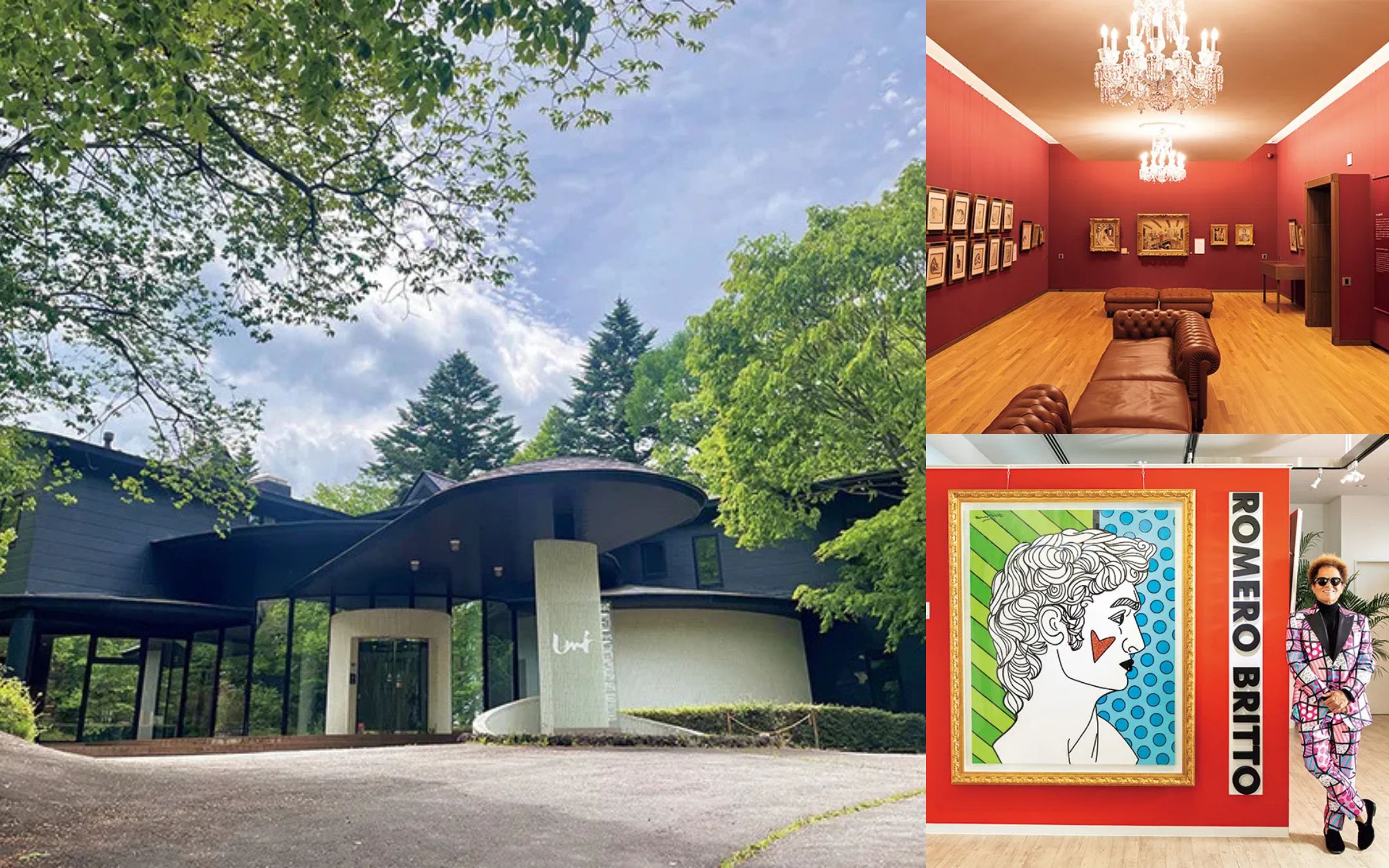

Karuizawa has long been Japan's most prestigious s ...

- Aug. 26. 2025

Many crafts in Japan are recognized as tangible cultural heritage and remain living practices, shaped by time, skill, and the utmost respect for materials. Across Japan, centuries-old craft traditions continue to evolve in the hands of master artisans and makers. This article shines a light on the powerhouses preserving these legacies, reviving time-honored techniques while propelling Japanese craftsmanship onto the global stage.

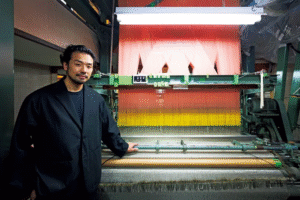

Founded in 1688, Hosoo is a long-established Nishijin textile weaving house with deep roots in Kyoto’s craft heritage. For more than 1,200 years, artisans in Kyoto have produced Nishijin textiles exclusively in Japan, and they remained largely unknown abroad, reserved for the privileged elite. Masataka Hosoo, the 12th-generation head of the company, ultimately introduced these exquisite textiles to the world.

“When I joined the family business, the Nishijin textile market had shrunk to one-tenth of its size over the past 30 years and was in a state of crisis. The turning point came in 2008 after the ‘Japanese Sensibility’ exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, when the world-renowned architect Peter Marino approached us with a request to create a fabric with the international standard width of 150 centimeters. We spent a year developing a new loom to increase the fabric width from the traditional 32 centimeters used for obi (sashes) to 150 centimeters. This innovation marked a major turning point in our global expansion.”

The loom developed in 2010 marked the beginning of a period of growth. What started as a single machine has expanded to 14. In 2023, Hosoo opened a showroom in Milan’s Brera district, establishing a new base for its global operations. At Milan Design Week in spring 2025, Hosoo unveiled its “Hemisphere Collection,” created in collaboration with the Milan-based architectural duo Dimore Studio, earning wide acclaim.

Once crafted exclusively for aristocrats and wealthy merchants, Nishijin textiles are now cherished by discerning clients around the world, carrying the legacy of these extraordinary woven fabrics far beyond Japan.

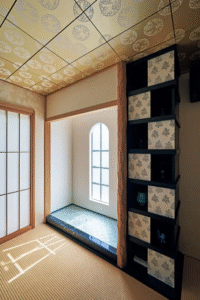

Karakami is a decorative paper made by hand-printing patterns onto washi (Japanese paper) using woodblocks. This uniquely Japanese art form traditionally used for interior decor, including fusuma doors, folding screens, and wallpaper.

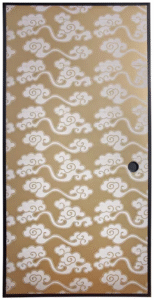

Choemon Senda, the 13th-generation karakami artisan and successor to Karacho, carries forward nearly four centuries of karakami-making tradition while reimagining it for the modern era. Since its founding in 1624, Karakacho has preserved more than 600 hangi (woodblocks), each intricately carved with classical patterns. The woodblock shown here, known as Ganryu (Coiled Dragon), dates back to 1794 and remains in use today.

Most woodblocks are roughly one-twelfth the size of a fusuma (single sliding screen), and artisans create large-scale designs through repeated printing. In 2024, Choemon Senda officially succeeded to the first master’s name and became the 13th-generation head of the family business, working alongside his wife, Aiko Senda.

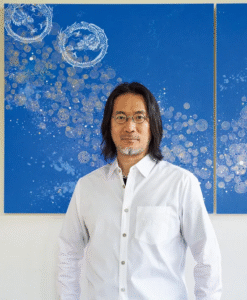

Senda also develops his own artistic expression, often characterized by profound shades of blue. In October 2025, a 20-meter long installation of his work adorned the entrance of the Espacio Nagoya Castle hotel.

Believing that true tradition lies in layering the present onto the past to open new paths toward the future, Senda has launched contemporary initiatives such as applying karakami motifs to new materials, collaborating across industries, and carving new woodblocks–including The Hundred Patterns of Heisei and Reiwa, which embody the prayers and hopes of people living today. These modern creations introduce innovative expressions never before seen in classical karakami.

To welcome visitors from around the world who seek the beauty and irreplaceable value embedded within karakami, Karacho operates a private, appointment-only salon in Saga, Kyoto–an intimate space that fosters dialogue around new ways to experience karakami.

Nambu Tekki (ironware) traces its origins to the mid-Edo period, when the lord of the Nambu domain in Iwate invited kettle artisans and blacksmiths from Kyoto to craft kettles for the tea ceremony.

Renowned for its solid, robust appearance, Nambu Tekki entered a new chapter in the late 1990s when the ironware maker IWACHU received a request from a French tea retailer to produce colorful teapots. The resulting pieces created a sensation in France, where they were praised as elegant and refined.

Today, IWACHU’s teapots have become synonymous with Nambu Tekki throughout Europe, so much so that many simply refer to them as IWACHU.

Founded in the late Edo period, Kojima Shoten is a long-established Kyo-Chochin (Kyoto Lantern) maker, now led by 10th generation artisans Shun Kojima and Ryo Kojima, who carry on the family’s traditional techniques and ethos.

Their Meiji lantern, crafted entirely by hand, from split bamboo washi paper, has been produced using the same metal mold for more than 110 years, ever since its creation in the Meiji era.

Ryo Kojima, the current head of Kojima Shoten, has collaborated with leading European fashion, jewelry, and watch brands, bringing traditional Kyoto craftsmanship into contemporary design spaces. One of the studio’s signature works is a monumental custom lantern created for the main dining hall of Ace Hotel Kyoto. Featuring a layered, three-dimensional design–one lantern nested within another–it now serves as the striking centerpiece of the space.

Rooted in the traditional craft of lantern-making, from splitting bamboo to layering washi paper, Kojima Shoten preserves the sturdy and minimalist qualities of the “Kojima-style” lantern while exploring new materials and forms.

Shuji Nakagawa, the third-generation artisan of Nakagawa Mokkougei (woodworking), carries forward Kyoto’s tradition of Ki-oke-shokunin (wooden barrel-making) while redefining it for a global audience.

When his grandfather Kameichi founded the workshop, Kyoto was home to around 250 barrel-making studios. By the time Shuji established his own Hira studio in 2003, only three remained. Working with more than 300 types of planes, Nakagawa shaves each surface by hand to achieve a flawlessly smooth finish. Despite the industry’s steep decline, his studio now employs seven young craftspeople and has begun attracting international apprentices.

Nakagawa attributes this revival to “tradition, innovation, and a global outlook.” A major turning point came in 2010, when he collaborated with a long-established French luxury maison to create a wooden champagne cooler.

One of his standout designs, WAVE, breaks free from the conventional barrel form with graceful, flowing curves. By placing the metal hoops only at the base, Nakagawa highlights the natural beauty of the wood grain. “To bring the barrel, a tool typically used behind the scenes, onto the dining table as a centerpiece, I needed to go beyond the familiar round or oval shapes,” he explains. “Through countless prototypes and adjustments, I finally achieved a form that felt just right.”

Nakagawa has also collaborated with Italian product designer Alessandro Stabile to create a modern ahitsu (rice container), featuring a clever design that allows the rice paddle to rest neatly on the lid’s handle. “I came to realize that there was still room for evolution in the wooden barrel,” says Nakagawa.

Today, his Ki-oke creations have captured international attention, bringing the beauty of Japanese craftsmanship to tables and design spaces around the world.

Today, Japan’s crafts reach audiences far beyond its borders, yet their essence remains unchanged–rooted in precision, respect, and a deep reverence for materials. As these craft powerhouses innovate, they ensure that Japan’s cultural heritage lives on for future generations. On your next trip to Japan, consider stopping by some of the studios or shops where these traditional crafts continue to thrive and evolve.